This post came from the Aestiva Solutions quarterly newsletter, the Campfire. To subscribe, click here.

We’ve all been there. It’s a Monday morning in mid-September and you open up your email to see an instruction request for Wednesday. THIS Wednesday. You have never provided a library instruction session for this course, and you are not especially familiar with the subject matter. After replying enthusiastically “yes!” to the professor you copy a LibGuides Community topic guide, scour OER lesson plans and activities, and develop search strategies for the topic in EBSCOhost databases in an attempt to patch together a lesson. You’ve quickly cobbled together a variety of material, but in a panicked haze are still unaware of exactly how to teach this class session. In a moment of reflection you begin to do what you should have first considered: write student learning outcomes.

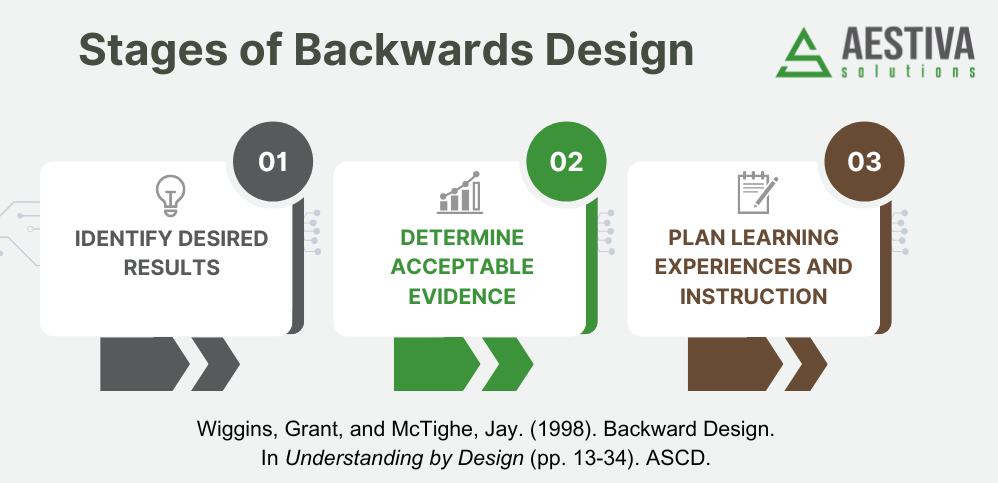

As part of our role at PALNI, Ruth and Eric plan several professional development opportunities every year. As we sit and brainstorm what we want to cover, we often jump right in to selecting content, choosing activities, creating learning objects… and then usually about 30-60 minutes into this process one of us says “guess what we forgot to do” and we both laugh and go back to the beginning and work on our learning outcomes. Developing learning outcomes are the core of the first and second stages of McTighe and Wiggins’ backwards design concept. Backwards design forces one to consider the big picture for their lesson and determine what success looks like for the lesson. Once you clearly define learning outcomes, it makes it so much easier to add all the rest!

There are numerous approaches to structure your learning outcomes, each with their strengths and limitations. One that Eric enjoys using is ABCD: audience, behavior, condition, and degree. While he doesn’t always hold to it perfectly, the framework is helpful to consider the elements needed for developing effective learning experiences.

- Audience. Beyond the word “students”, consider the specific needs of your audience. First year traditional undergraduates differ greatly from adult graduate students.

- Behavior. What do you want your audience to complete? Be specific! Action verbs are a great place to start, such as from Bloom’s taxonomy.

- Condition. What “must haves” from the professor or assignment need to be included in the lesson?

- Degree. What’s the standard for acceptable performance? An example could include a number of relevant articles obtained through a literature review.

Writing learning outcomes may feel tedious and time consuming, especially under tight deadlines during stressful times of the year. However, the time invested up front will make up for itself in the long term. Even if you forgot to develop learning outcomes at the start of your lesson planning, like we have confessed to regularly doing, it is never too late to include these and they will always help with your final product.

Want to improve your instruction strategies? Partner with Aestiva Solutions for some creative professional development. Leverage our combined experience to enhance your local impact!

Know a colleague who might be interested in receiving tips like these? Please pass this newsletter on to them and encourage them to subscribe!

Ruth and Eric